California Housing in 2025

Comprehensive Environmental Law Reform Can Spur Housing Development

Despite near-universal acknowledgement of a crisis, years of debate and numerous policy efforts in the California Legislature, the state continues to set record home prices year after year with demand far outweighing supply. The transformative policy changes needed to spark a housing construction boom remain illusory.

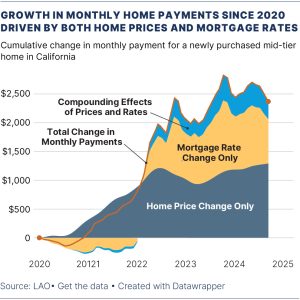

Median home prices in the Golden State hit $868,150 in 2024, giving California (again) the unwanted accolade of being the most expensive housing market in the nation. Mid-tier homes in California — those in the 35th to 65th percentile range — are now more than twice as expensive as the typical mid-tier home in the rest of the United States. Additionally, the prevailing mortgage rate on a 30-year fixed rate mortgage skyrocketed from 2.7% in January 2021 to 7.6% in October 2023, dropping only slightly to 6.2% in September 2024. This increase in mortgage rates coupled with increased home prices have only compounded California’s housing affordability crisis.

Median home prices in the Golden State hit $868,150 in 2024, giving California (again) the unwanted accolade of being the most expensive housing market in the nation. Mid-tier homes in California — those in the 35th to 65th percentile range — are now more than twice as expensive as the typical mid-tier home in the rest of the United States. Additionally, the prevailing mortgage rate on a 30-year fixed rate mortgage skyrocketed from 2.7% in January 2021 to 7.6% in October 2023, dropping only slightly to 6.2% in September 2024. This increase in mortgage rates coupled with increased home prices have only compounded California’s housing affordability crisis.

Rare Bright Spot: Rents Came Down in Some Cities

Although California remains one of the most expensive states in the country for renters, the state surprisingly saw reductions in median rents in 2024 across many major cities — opposite of what most cities around the country were seeing. For example, in San Diego County, the average rent decreased from $2,338 in 2023 to $2,170 in 2024, a more than 7% drop. And in the city of San Diego, the average rent fell from $2,266 in spring 2023 to $2,189 in spring 2024, a decline of more than 3%. (Southern California Rental Housing Association) The most significant drops in rental prices were observed in Oakland and Sacramento, where rates fell by 9.1% and 8.1%, respectively, compared to 2023. Los Angeles saw a 5.0% decrease, San Jose about 2.3% decrease, and San Francisco 1.7% decrease. (California Apartment Association)

Whether this trend will continue remains to be seen. It is unclear whether the decreases were in part due to rents reaching all-time highs post pandemic and coming back down to more healthy levels, whether renters were moving out of the state or a more macro sign of California’s economy.

Is California Exodus Over?

At the start of 2024, the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) warned that California “appears to be on the verge of a new demographic era, one in which population declines characterize the state.” Lower levels of international migration, declining birth rates, and rising deaths contributed to this trend. However, PPIC identified the primary driver of population loss as Californians relocating to other states. Between 2000 and 2020, California experienced a net loss of 2.6 million residents to other parts of the United States. Since 2010, 7.5 million people have left California for other states, while only 5.8 million moved in. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the state’s population fell by 114,000 between 2021 and 2022.

Despite these concerning trends, California began to see a shift in 2023, marking the first population growth since 2020. According to the California Department of Finance, California added 67,000 residents last year, bringing the total population to 39,128,162. The growth largely stems from a rise in legal immigration and natural population increases. While counties like Los Angeles continued to see resident losses, areas such as Riverside, San Bernardino and Sacramento experienced notable population gains. Similarly, cities like Bakersfield, Fresno and Sacramento grew as more people moved away from urban centers such as San Francisco and Los Angeles, where both home prices and rental prices are some of the highest in the nation.

What Legislature Should Address in 2025 Relating to Housing

CEQA Abuse

The California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) is not the sole cause of the housing shortage, but it often is a major impediment to housing development in California — no matter the size of the project. CEQA requires local governments to conduct a detailed review of discretionary projects prior to their approval. CEQA protects human health and the environment by requiring lead agencies to analyze the impacts of projects and then requires project developers to mitigate any potentially significant environmental impacts. But unlike most environmental laws and regulations in California, CEQA is enforced through private litigation, which has mushroomed over time. The litigation can substantially slow or even stop housing projects when opponents do not want added density in their neighborhood, do not want a competitor locating in the area, or want to leverage the project developer for unrelated considerations, like union labor, preferential hiring, or additional environmental mitigation.

CEQA can add significant cost and time to the housing development process. Even the threat of litigation can discourage developers or substantially raise the costs to develop housing, as developers expend significant resources preparing for and defending their projects from opponents. And because housing costs ultimately are borne by future home buyers, CEQA inevitably raises housing prices in California even if the project is unchallenged. It may be no coincidence that California’s cost of housing began to increase significantly the same decade in which the California Legislature passed CEQA and increased community resistance to new homes got stronger. Between 1970 and 1980, California home prices went from 30% above U.S. levels to more than 80% higher, according to a report from the Legislative Analyst’s Office.

Streamline Planned Communities

California needs to prioritize and streamline the construction of master-planned communities to address the critical housing shortage and create resilient, sustainable growth throughout the state. Large-scale developments offer a unique opportunity to build tens of thousands of new homes while integrating essential infrastructure like roads, schools, infrastructure and utilities from the outset. Unlike smaller piecemeal projects, master-planned communities can strategically reduce vehicle miles traveled (VMTs) by incorporating job centers, schools and retail within the community, promoting walkability and reducing the state’s reliance on long commutes. These types of developments can make substantial investments in sustainability — such as energy-efficient design, water conservation systems, and renewable energy integration — that smaller developments simply cannot achieve at scale.

While infill development plays a crucial role as part of California’s overall housing policy, it alone cannot meet the state’s overwhelming housing shortage. Infill projects often face significant limitations, including high land costs and intense community opposition. With millions of new units needed in California to stabilize the housing market, master-planned communities can complement infill housing policies by delivering housing at scale while addressing critical gaps in affordability, infrastructure, and environmental sustainability. Combined with targeted infill efforts, these developments provide the scale and flexibility California desperately needs to tackle the housing crisis.

CalChamber Position

California’s housing crisis is driven by a clear lack of supply that is driving residents out of state and discouraging new people and investments from coming in. Unaffordable housing forces many Californians into extra-long commutes, adding more air pollution and traffic congestion while reducing worker productivity and quality of life.

Comprehensive reforms of environmental and zoning laws are necessary to remove obstacles that hamper housing construction, add delay and raise home prices and rental prices. A comprehensive reevaluation and reform of CEQA is a critical step to spurring housing development in California as abuses continue to plague timely development of housing. Maintaining CEQA’s legacy of protecting human health and the environment is not incongruent with more streamlined housing development. The state can no longer afford to play on the margins — it must take bold action by passing policies that spur critically needed supply.

February 2025

Agriculture and Resources

California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA)

Climate Change

Education

Energy

Environmental Regulation

Health Care

Housing and Land Use

Immigration Reform

International Trade

Labor and Employment

Legal Reform

Managing Employees

Privacy

Product Regulation

Taxation/Budget

Tourism

Transportation

Unemployment Insurance/Insurance

Water

Workers’ Compensation

Workplace Safety

Housing and Land Use Bills

Committees

Staff Contact

Adam Regele

Adam Regele

Vice President of Advocacy and Strategic Partnerships

Environmental Policy,

Housing and Land Use,

Product Regulation