The history of the Federal Arbitration Act (FAA) and numerous U.S. Supreme Court decisions interpreting the act’s broad scope and strength set the stage regarding the significant limitations states have in enacting any statute that limits, interferes with, or prohibits the arbitration of disputes.

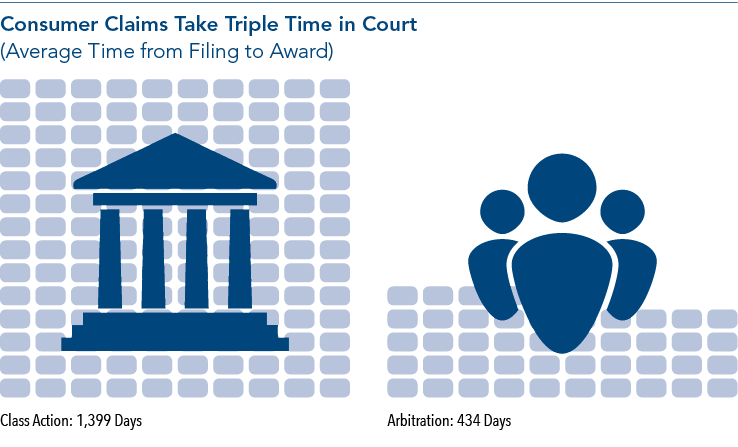

One of the most appealing attributes of arbitration is its efficiency compared to litigation. This attribute was explicitly recognized in a 2011 U.S. Supreme Court decision (AT&T Mobility LLC v. Concepcion) as a key component of arbitration.

According to the U.S. District Court Judicial Caseload Profiler, there were 27,956 cases filed in California in 2015. As of June 2015, approximately 2,175 cases had been pending in a federal district court in California for more than three years and the median time from filing of a civil complaint to trial was approximately 31 months.

State courts also have seen an increase in delays for civil trials, given the reduced budgets they have been required to manage. In large cities such as Los Angeles, the number of civil cases pending for more than two years has tripled since 2012.

Comparatively, the 2011 American Bar Association’s guide to the “Benefits of Arbitration for Commercial Disputes” states that one of the benefits of commercial dispute arbitration is it generally takes between 7 months to 7.3 months for issuance of a final award, compared to the median national average of 23.4 months for a civil case in a district court, which is better than the average in Northern California.

A 2007 study by the American Arbitration Association, “AAA Arbitration Roadmap,” provided the following statistics: for cases involving a claim of up to $75,000, the median time for a final resolution was 175 days; for claims between $75,000 and $499,999, the median time for final resolution was 297 days; and for claims between $500,000 and $999,999, the median time for final resolution was 356 days.

Lower-Paid Employees’ Access to Justice

Multiple scholars have found that employees who earn mid- to lower-level wages simply cannot obtain legal representation in court and cannot afford to pursue a case on their own.

One scholar has stated the reason lower-paid employees cannot obtain counsel is the “potential dollar recovery will simply not justify the investment of time and money of a first-rate lawyer in preparing a court action.” See Theodore J. St. Antoine, “Mandatory Arbitration: Why It’s Better Than It Looks,” (2008).

Lewis Maltby, president of the National Workrights Institute, wrote an article titled “Employment Arbitration and Workplace Justice,” in which he set forth data that showed 95% of employees seeking legal representation are turned down by attorneys. Accordingly, arbitration is an important access to justice for such employees.

Class Action Awards vs. Arbitration

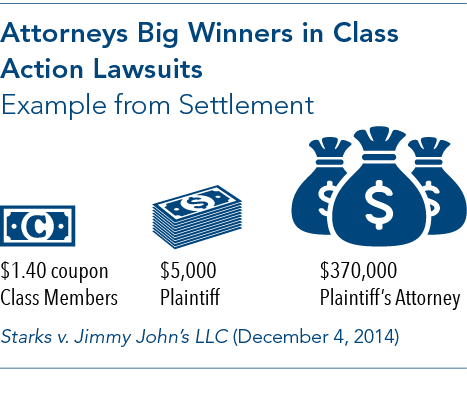

While scholars may disagree regarding the amount of awards issued for single plaintiffs in arbitration versus litigation, the comparison is significantly different when the arbitration award is compared to the award received in a class action. As referenced in various studies, the median award in arbitration for an employee ranged between $40,000 and $95,000.

In one case, Starks v. Jimmy John’s LLC (Los Angeles Superior Court, BC501113), the plaintiff filed a consumer class action against the sandwich franchise, alleging it failed to put sprouts on her sandwich. The class action settled in July 2014 as follows: 1) $5,000 to the named plaintiff; 2) $1.40 coupon to each class member; and 3) $370,000 to the plaintiff’s attorney for fees and costs.

Opponents’ Attacks on Arbitration

Opponents of arbitration claim that arbitration is unfair because the arbitrators are more likely to side with the employer or company who pays for the arbitration and from whom the arbitrator wants repeat business. In California, however, existing law significantly reduces the risk of any “repeat player” phenomenon or bias.

Opponents also claim that binding arbitration is not subject to appeal. While it is true that binding arbitration is not subject to a general right to appeal as civil litigation, there are multiple bases upon which an arbitration award shall be vacated as set out in the California Code of Civil Procedure and court rulings.

Contrary to opponents’ claims that arbitration is confidential without any public access or knowledge, California law requires a quarterly report by all private arbitration companies that administer arbitration in California.

The quarterly reports must be published on the arbitration company’s website, available to download without a fee, as well as available in a hard copy format with specified information, including the nature of the dispute, amount of the award and the percentage of the arbitrator’s fee allocated to each party.

Moreover, arbitration agreements cannot be a hidden clause or in a foreign language. Just like any other contract, an arbitration agreement must have consent that is mutual, free, and communicated between the parties.

In addition, both the California Supreme Court and the U.S. Supreme Court have explicitly stated that an arbitration agreement cannot waive a consumer’s or employee’s substantive rights or remedies. Arbitration is a choice of forum regarding where to resolve disputes. It does not and cannot reduce or eliminate substantive rights of the consumer or employee.

State Legislation

Despite the broad scope and strength of the FAA, each session legislators introduce multiple bills regarding arbitration.

In the 2015–2016 session, job killer legislation discriminating against arbitration agreements in consumer contracts and in employment agreements was stopped in the Assembly. The Governor vetoed a bill that sought to prohibit pre-dispute employment arbitration agreements made as a condition of employment, expressing his concerns with pre-emption under the FAA, as well as noting the existing California protections with regard to pre-dispute, mandatory arbitration agreements.

The Governor also vetoed a proposal that sought to regulate arbitration providers and arbitrators by limiting their ability to arbitrate different cases involving the same party, as well as imposing even stronger disclosure requirements. In his veto message, the Governor indicated his reluctance to impose stricter requirements without evidence of any problem.

The Governor did sign into law a bill that makes voidable any choice of law or choice of venue provision in an employment agreement that designates a location or law other than California for litigation, including arbitration (SB 1241; Wieckowski; D-Fremont; Chapter 632, Statutes of 2016).

CalChamber Position

The CalChamber supports the freedom of businesses to utilize arbitration as a means of resolving disputes. When an arbitration agreement is fair for both parties, courts should respect the parties’ intent and enforce the agreement. Alternative dispute resolution options are beneficial to the parties involved and reduce the already-overcrowded dockets of our court system.

Any legislation that seeks to undermine the right of parties to agree to arbitration or enforcement of the terms of a valid contract should be rejected and likely is pre-empted under the FAA. Any efforts to limit, interfere with, or prohibit arbitration of any claim should be pursued at the federal level, given the breadth and strength of the FAA.

Staff Contact: Jennifer Barrera

This is an abridged version of the arbitration article from the 2017 Business Issues and Legislative Guide. Read the full article at www.calchamber.com/businessissues.