An array of evidence points to the fact that the California economy has been humming along nicely, and that is expected to continue in the coming year, although the state must face long-term challenges, and the sooner the better, according to a recent report by the California Chamber of Commerce Economic Advisory Council.

Like a Car in Overdrive

The state’s unemployment rate is on track to finish 2017 below 5% for the first time in 11 years. California’s unemployment rate is higher than the U.S. rate, but the differential between the two is now at its lowest in more than 10 years.

Looking across the state, a number of California counties have unemployment rates under 3%, but a few face rates above 7%, in many instances due to the composition of industries and substantial seasonal employment in those counties.

The state’s industries have continued to add workers to their ranks, and this has pushed the unemployment rate down. Overall, nonfarm jobs grew 1.7% in year-to-date percentage terms through October 2017. Construction has led the way with a 5.0% increase, and nearly every other industry added jobs over the past year.

The only exceptions were Manufacturing, which was down marginally, and Mining and Logging, which has been reeling from weakness in the energy sector for some time.

With few exceptions, job gains by industry in 2017 have been less than in the previous three years. In particular, there has been a dramatic slowdown in job growth in the Information and Professional Scientific, and Technical Services industries that led the state in the early stages of its economic recovery.

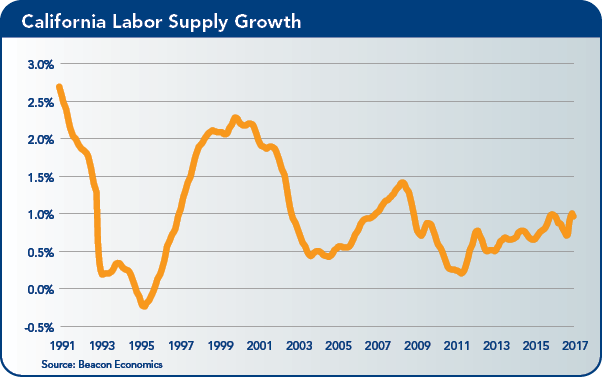

Given slow growth in the labor force, California’s labor market is like a car in overdrive, moving forward at a steady pace of about 1.5% job growth per year, incapable of moving any faster.

So Why Worry?

The near-term picture looks good, but long-term problems require attention now. Home sales have edged up, but the statewide homeownership rate remains stubbornly low because of unaffordable high prices. At the same time, rents have increased steadily in many parts of the state in the face of low apartment vacancy rates.

It should be no surprise that net domestic outmigration, already negative for several years, surpassed 100,000 persons annually over the last two years. The high cost of housing in California is driving workers out, especially low-wage earners.

Based on estimates by Beacon Economics and others, the state should be adding approximately 200,000 new housing units annually, but is building about half that amount. Connecting the dots, if the state does not build enough homes, outmigration will continue, stunting both increases in the labor force and the growth potential of the California economy.

As if the housing situation in California isn’t already challenging enough, the federal tax plan that passed in mid-December contains measures that will change the playing field for state residents. The homeownership rate in California already is considerably lower compared to the United States as a whole, mainly because the median home price is more than twice that of the nation.

Historically, middle-income households in California have been able to count on the deductibility of mortgage interest and property taxes to soften the blow. The new tax plan will cut the limit on mortgage interest deductions from $1 million to $750,000 and also impose a $10,000 limit on state and local tax deductions. This will put the American Dream of homeownership further out of reach for more California residents.

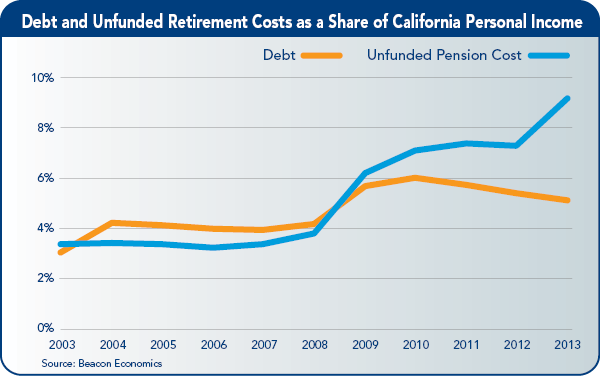

Yet another long-term concern is the gulf between pension obligations and pension funding for state and local governments, which has widened in recent years and will continue to do so over the foreseeable future.

Jurisdictions face a difficult choice: They can divert current revenues to pay down pension obligations, but this may diminish services to residents and much-needed expenditures on infrastructure. A few communities have won tax hikes that will help support services and infrastructure investment, but they have been the exception rather than the rule.

Finally, while the state budget appears to be in good shape for now, and while California lawmakers have made contributions to the state’s Rainy Day Fund for several years in a row, the situation could turn on a dime. It is well-known that state revenues fluctuate widely with movements in the stock market.

Each of these long-term problems can be addressed so as to stave off the worst consequences. But in each case elected officials and other stakeholders need to act now, while the economy is doing well, to tackle these challenges and ensure the long-run growth of California.

U.S. Outlook: A Turning Point

From a political standpoint, 2017 will go down as one of the most chaotic periods in recent U.S. history, although it may well end up being overshadowed by 2018.

Economically, on the other hand, 2017 was fairly ho-hum. Overall U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) output will have expanded by 2.3% in real terms once the fourth quarter is added. This is a better showing than in 2016, but a weaker one than the previous two years with exports and business investment looking stronger, while consumer spending has softened.

While ho-hum may not excite, the sure and steady growth carries with it another advantage. The U.S. economy is now in the ninth year of its current expansion, and at this point there is little reason to believe that will end in 2018.

In fact, this expansion likely will end up being the longest in U.S. history. Still, 2018 will be far from ordinary. The coming year will bring a number of important turning points, which will have far-reaching implications for the economy in the years ahead.

Labor Shortages Mounting

The nation’s slowing job growth is not due to a lack of labor demand—the job openings rate has been at or near an all-time high for the last few months. Instead, the slowdown in employment growth stems from a lack of available workers.

The labor shortage is hardly a surprise. Since the baby boomer generation, there has been a sharp slowing in the growth of the working age population—from 1.5% in 1995 to half a percent over the last few years. The nation’s workforce today is also, on average, considerably older, which partly accounts for the decline in the participation rate.

The labor shortage is being worsened by the clear antipathy that the current administration in Washington has toward immigrants coming to the United States. While we don’t have reliable statistics at this point, anecdotal evidence suggests a sharp slowing in the inward flow of immigrants, legal or otherwise.

A Deficit Low Water Mark

The changing demographics of the U.S. workforce are heralding another major change in the economy: growth in the federal budget deficit. The national debt as a share of GDP has been steady over the last few years after a big jump in the midst of the “Great Recession.”

This is about to change. Over the next decade, more than 40 million people will be added to the retirement rolls, and will begin receiving Social Security and publicly funded health care. This surge will cause a sharp increase in federal entitlement spending without a corresponding increase in the revenues to pay for them.

This disparity is why the Congressional Budget Office was forecasting a sharp increase in debt levels even before the Republican tax plan emerged, a proposal that will take this bad situation and make it worse. The GOP’s tax overhaul, which was just passed by Congress as of this writing, is mainly a massive cut in corporate taxes and an attempt to offset the loss in revenue by removing certain tax benefits, such as the mortgage interest deduction.

Putting aside the clearly regressive nature of this plan, no credible economist on record believes the proposal will have anywhere near the growth impact needed to pay for itself. When will the federal debt become untenable? That is almost impossible to guess at, but what is clear is that we will look back at 2018 as the year the tide turned.

On the surface, 2018 looks to be a lot like 2017 in terms of economic growth. But dig a little deeper and growing frictions become apparent. These will begin to create problems in the economy in 2019 or beyond. So enjoy the current economic calm—before long, the ride is going to grow bumpy.