For most of the post-recession era, the California economy has been among the fastest growing of the 50 states, both in terms of job gains and growth in economic activity, according to a recent report by the California Chamber of Commerce Economic Advisory Council.

Credit for this growth trajectory has largely been attributed to high tech, which has experienced phenomenal growth since the recession.

But it also was made possible by enormous slack in the labor market as the state recovered from the highest rates of unemployment seen in at least 40 years. For more than 60 months from early 2012 through mid-2016, California added jobs at roughly twice the rate as the United States.

Yet, by the third quarter of 2016, that slack had been squeezed out: Instead of handily outpacing U.S. job gains, California’s growth rate slipped to just above 1.5%, putting it roughly on par with the nation. But by early 2017, slack in the labor force was wrung out as California saw its unemployment rate hit a 16-year low, effectively at full employment.

Job gains continued in most industries, to be sure, but the pace of growth was much slower than in recent years. Entering the final quarter of 2017, some observers have worried that the slowdown in the labor market is a precursor to a stalling statewide economy.

Below are some of the highlights from the economic report.

Not So Fast!

Yes, California’s pace of job growth has slowed considerably, but not because the expansion is stalling out. In fact, the state continued to add jobs through the first several months of this year, but at a slower rate. Wage and salary jobs rose by 1.7% year-over-year in July, adding 276,300 jobs year-to-year, second only to Texas.

Despite the slowdown in job growth, California’s gross state product continues to advance nicely, increasing by 3.1% from the first quarter of 2016 to the first quarter of this year. Taxable sales growth slowed considerably, however, advancing by just 2.7% year-to-year in the first quarter of 2017 compared to a 6.7% increase in the final quarter of 2016.

With the state at full employment, job growth and general economic gains will largely be constrained by the availability of workers. This is good for workers who might achieve pay increases in the coming months and quarters, but it poses a challenge for firms that want to grow but cannot because they are unable to hire the necessary workers.

What is holding back growth and can anything be done about it? There is an easy answer to the first question, but the second is a different story.

Build It…They’re Already Here

For decades, California augmented its homegrown labor force with workers from elsewhere, drawing from both other states and other countries. Through much of the post-World War II era, the state was a magnet for workers from around the country and the world. There were opportunities for aerospace engineers, fruit pickers, and everything in between.

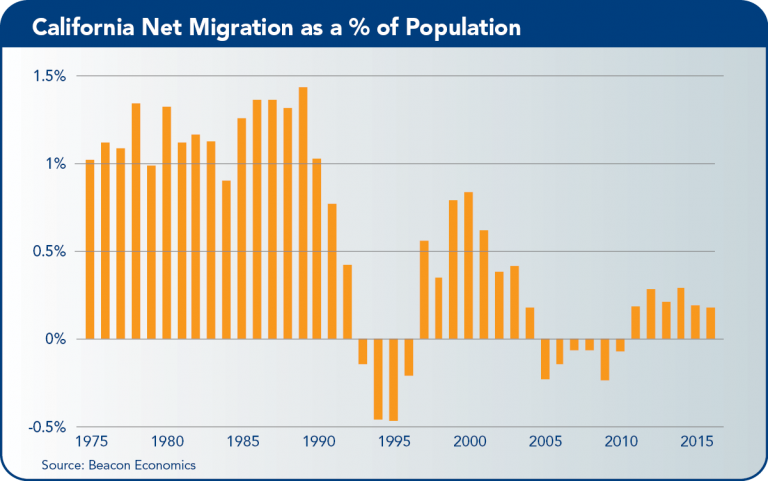

In the 1970s and 1980s, California’s labor force grew by an average of 3.1% per year, during which time net migration matched or exceeded California’s internal population gains. But net migration turned negative with the 1990s recession, and in turn, growth in the labor force has slowed to just 0.9% annually since 1991. Significantly, in the last decade and a half, consistent state-to-state migration out of California has been offset only by international migration into the state.

It is no coincidence that slower labor force growth has occurred as the cost of living has soared in California. As recently as the mid-1970s, the median price of a California home was just a few thousand dollars higher than the national median. But since 1990, the California median has consistently exceeded the U.S. median by more than 50%, with the state median at least double the U.S. median in 10 of the last 27 years. Meanwhile, rents have reached such heights that rent burdens in many communities across the state are among the nation’s highest.

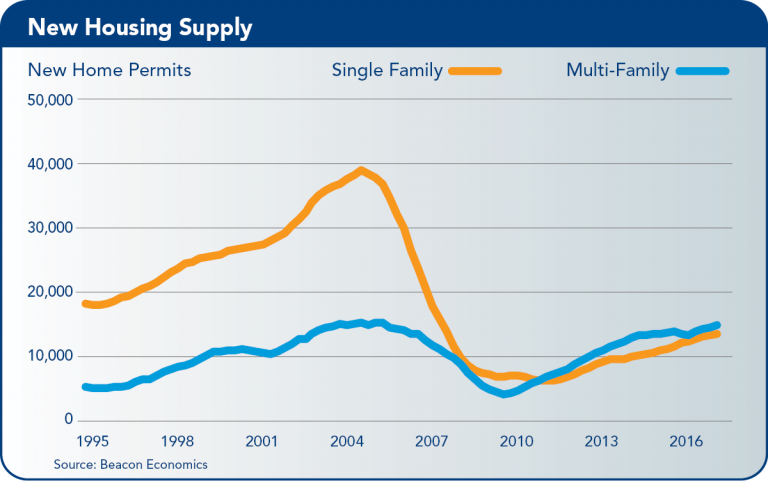

Without attempting to sound trite, it all boils down to supply and demand. On the demand side, the much-anticipated arrival of Millennials on the housing scene, coupled with recent job and income growth and low interest rates, are all driving demand for housing, both owner-occupied and rental. On the supply side, existing home sales have fallen below expectations, given the strength of the economy, while new single-family and multi-family construction has been relatively weak since the recession.

No, the situation ultimately must be addressed by increasing supply, a tall order indeed. But until California does so, in earnest, growth of the statewide economy will be constrained.

That is not to say that California won’t grow. It will. The state and its regions should experience continued growth in economic activity and jobs throughout 2017 and into 2018. Most of the job gains will occur in Health Care, Leisure and Hospitality, and Construction. But California will fall short of its potential until it crafts long-term supply-oriented solutions to the chronic problem of high housing costs and low housing affordability.

The National Outlook: Cruising Through Rough Waters

It may be tempting to interpret the hurricanes pounding the Southeast, major earthquakes in Mexico, bigger bombs going off in North Korea, and President Trump making a budget deal with the Democrats as the four horsemen of the economic apocalypse.

Yet, despite all the scary headlines, under the surface the U.S. economy is ticking along at a steady if unexciting pace.

Overall, Beacon Economics expects the U.S. economy to grow faster in 2017 than during the last two years. And the outlook for 2018 looks remarkably similar, short of some major change in government policy.

Here are some of the key economic trends we expect to see over the coming months.

Businesses are Investing

One of the best signs for 2017 is the solid recovery in nonresidential investment. Oil prices have stabilized and production and exploration are yet again on the rise. Globally, the European Union is seeing solid growth, China has stabilized, and commodity economies have started to bounce back, fueling U.S. export growth.

The ISM Manufacturing Index for August had the highest reading in six years. The European Central Bank just announced the end of its quantitative easing program and the U.S. dollar is beginning to depreciate from recent high levels, which should help maintain these trends in the second half of the year.

Disaster Economics

Only halfway through hurricane season, Houston is still in the midst of a major cleanup after Hurricane Harvey inflicted unprecedented damage on this enormous metropolis, and the damage Hurricane Irma wreaked on Florida is still being assessed. The human tragedy of these storms is clear, but it is a mistake to think they will have a negative impact on economic growth.

In contrast, the rebuilding that occurs will actually stimulate economic growth in the short term, particularly in the residential sector as billions of dollars will be poured into fixing or replacing damaged homes.

Consumers to Rebalance

While business spending is heating up, we expect consumer spending to disappoint in the second half of the year. Solid growth in consumer spending kept the economy humming through the commodity bust—but spending got ahead of incomes by a good margin.

Even better news is that this rebalancing will occur without many “side effects” because consumer debt burdens are still near an all-time low level and the tightness of the labor markets is driving solid wage gains.

Beware the Labor Shortage

One of the key messages of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign last year focused on the lack of job opportunities for Americans—driven, he claimed, by bad taxes, bad regulations, and the huge number of undocumented workers in the nation. As much as that message resonated with part of the American public, it simply isn’t true.

The country’s headline unemployment rate is now at 4.4%—the lowest since the 1960s with the brief exception of the tech bubble-fueled economy of the late 1990s.

There are a number of benefits to a tight labor market—not the least of which is rising wages for workers. This might seem like a contradiction to the vast majority of press coverage of monthly jobs data, which almost always laments the lack of income growth. But the popular press is failing to account for low inflation and certain issues with the labor survey.

Rising wages are pulling people back into the workforce and labor force growth is as strong as it has been in over a decade. This is a positive for discouraged workers who may have formerly dropped out of the labor force, as they will be given opportunities to receive training and experience.

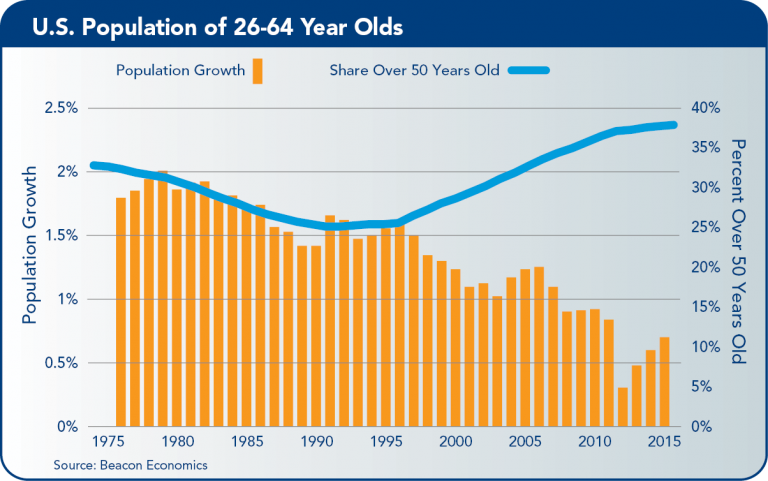

But the pool of “discouraged” workers is small—2 million to 3 million at most. Soon, even that reserve of workers will be gone, and in addition, the baby boomers are beginning to retire in force. The solution to this problem is the expansion of immigration, an entirely opposite stance from the one the current presidential administration is pursuing. As always, our generals continue to fight the last war—not the next one.

The Trump Effect

This brings us to federal policy, or perhaps the lack thereof. When President Trump entered office, he promised radical shifts in government policy. Some of those policies could have been modestly stimulating to economic growth, while others could have put the nation on a path straight into recession.

At this point, Beacon Economics believes the chance of a major change in policy (positive or negative) occurring is small but real. In the meantime, we’re sitting back and taking in this year’s must-watch TV—Survivor: White House.

Janet’s Choice

And what about equities? Banks have been slowing their lending, commercial real estate markets seem to be plateauing, there are a variety of political and global worries, and rising wages are putting pressure on profits. But despite all this, equity markets continue to break records month after month.

The Fed is in a tough spot. It needs to figure out how to slow equities before they end up popping on their own with potentially dangerous consequences. Yet, to date, raising the Federal Funds rate and starting to sell off the balance sheet clearly isn’t doing the job. Confounding the issue further is the question of leadership at the Fed in 2018 when Janet Yellen’s term comes to an end. The prediction as to what the Fed does next boils down to a coin toss.