Day 2 – Parliament and the Panama Canal

National Assembly

We were given the opportunity to visit the Asamblea Nacional, or National Assembly, which is the legislative branch of the Panamanian Parliament. We arrived at the Palacio Justo Arosemena via the office of an independent deputy, Juan Diego Vásquez, for a guided tour of the building. He explained the role of the legislative branch in the Panamanian parliamentary process. The palacio is located next to the Plaza José Remón Cantera, and consists of a large office tower, which is attached to a shorter auditorium floor. The front of the building is lined with Panama flags and a large statue that sits at the far left.

It is a unicameral legislature, with 71 members, who serve five-year terms. Panama’s legislative elections are held simultaneously with its presidential and local elections.

We were able to observe the Assembly in session, as well as receive a briefing in the H.L Manuel Ortega Chanchore Lounge area reserved for members and guests.

Entrepreneurship and Status of Women

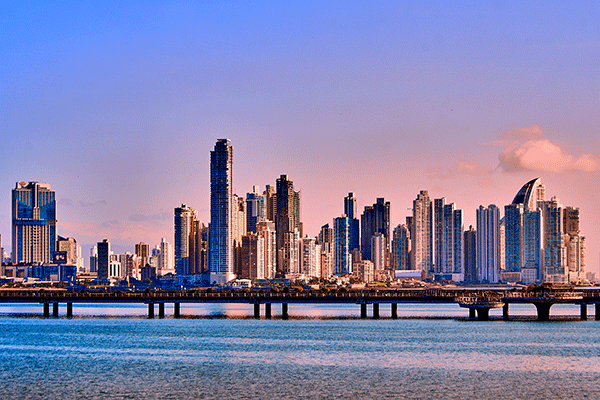

After visiting the Assembly, we drove across the Causeway, seeing beautiful panoramic views of Panama City, to enjoy a seafood lunch on Flamingo Island at Restaurante Bucaneros – Los Mejores Mariscos en Panamá. During lunch, we enjoyed a discussion with proprietor Sofia Kalormakis, a Panamanian business and communications consultant and restaurateur. We discussed contemporary Panamanian society, U.S.-Panama relations, as well as the status of women in business and government.

The Panama Canal

Opened in 1914, the Panama Canal stretches 51 miles and connects the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, cutting across the Isthmus of Panama as a conduit for maritime trade. The Canal operates with locks at each end, lifting ships up to Gatún Lake, an artificial freshwater lake 85 feet above sea level that was created by damming the Charges River and Lake Alajuela. Locks then lower the ships at the other end. The average depth is 43 feet, and the width varies between 500 to 1,000 feet.

There are 12 sets of locks in the Panama Canal. There are six sets of locks in the old section of the Panama Canal and six additional sets in the new section of the canal. Each set of locks has a series of “steps” that allow the ships to move up or down in elevation. On average, straight through from one ocean to the other, the Panama Canal transit can be completed in approximately 8–10 hours. The cap is 38 ships per day.

Journeying to the Panama Canal, you see the landmark surrounded by small operation buildings and outlined with two-lane roads. The Miraflores locks are just outside of Panama City. The large cargo ships have two lanes, like a two-lane road, with a center median that separates the directions of traffic. This center median works to help operators as the ships pass through and is large enough to have two separate sides to it. As ships enter, water is released to lift or lower the ships as they arrive and depart.

We first watched an outstanding Imax movie with Morgan Freeman narrating the history of the Canal. Then we sat at the Observation Deck and later were allowed right next to the “mules,” which once were live mules, but are now remotely controlled machines pulling and guiding the ships.

As parched conditions gripped the Central American country last year, the Panama Canal Authority slashed the number of vessels allowed to cross each day to 22, about 60% of normal. Shippers paid millions of dollars to jump the growing queue and avoid wait times that stretched more than two weeks. The disruption caused by the water shortage in the Panama Canal had a significant impact on scheduling reliability and spot rates.

The recent increase in water levels in the Panama Canal has sparked hopes of a return to normal operations for container shipping, after more than a year of restrictions due to a severe drought.

The Panama Canal Authority continues to monitor weather conditions daily to respond to the increased inflows to the watershed and implement necessary operational actions. They have managed to ward off a shipping crisis that threatened to upend $270 billion a year in global trade. It did so with careful water management — and a little bit of luck.

The canal’s turnaround is due, in part, to successful water-management measures. But it’s also the result of a wetter-than-expected dry season — which extends from December to April in Panama — and the end of El Niño, the weather phenomenon that left Panama with one of its least rainy years on record.

For the Panama Canal, water-saving measures such as cross-filling, a technique that re-uses water in the canal’s locks, and reducing daily transits helped offset the drought’s impact, the canal authority said. The goal now is for Lake Gatún and another reservoir connected to the canal to rise enough to keep trade flows at capacity through the next dry season.

Under typical circumstances, the Panama Canal handles about 3% of global maritime trade volumes and 46% of containers moving from Northeast Asia to the U.S. East Coast. Any increase is a relief to shippers, some of whom were forced to take the long route around South Africa or through Chile’s Strait of Magellan to get their goods to market.

Chilean fruit farmers are among those cheering the recovery, said Ignacio Caballero, director of marketing for the produce trade association Frutas de Chile. Many of them had to reconfigure U.S.-bound shipments last year due to the Panama Canal restrictions on booking slots.

Exporters of liquefied natural gas, a key heating and power-plant fuel, also benefit from the easing of canal constraints. Some LNG tankers have been sailing around the Cape of Good Hope.

Dinner in the evening was at Isaki – Japanese Restaurant, a rooftop restaurant in the Casco Viejo historic district.

Day 3 – Presidential Palace, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, U.S. Embassy >>

Blog By

Blog By

(Mrs.) Susanne Stirling

Vice President, International Affairs

susanne.stirling@calchamber.com